In either case, the resistance to flow (or shear) as a function of the input force is measured, which reflects the internal resistance of the sample to the applied force, or its dynamic viscosity. The dominant procedure for performing kinematic viscosity measurements is ASTM D445, often modified in the used oil analysis lab to save time and make the test measurement more efficient.Ībsolute viscosity is measured as the resistance to flow when an external and controlled force (pump, pressurized air, etc.) forces oil through a capillary (ASTM D4624), or a body is forced through the fluid by an external and controlled force such as a spindle driven by a motor. The time taken for the fluid to flow through the capillary tube can be converted directly to a kinematic viscosity using a simple calibration constant provided for each tube. Different sized capillaries are available to support fluids of varying viscosity. The orifice of the kinematic viscometer tube produces a fixed resistance to flow. Kinematic viscosity is traditionally measured by noting the time it takes oil to travel through the orifice of a capillary under the force of gravity (Figure 1). Other common kinematic viscosity systems such as Saybolt Universal Seconds (SUS) and the SAE grading system can be related to the measurement of the viscosity in cSt at either 40☌ or 100☌.

#DYNAMIC VS KINEMATIC VISCOSITY ISO#

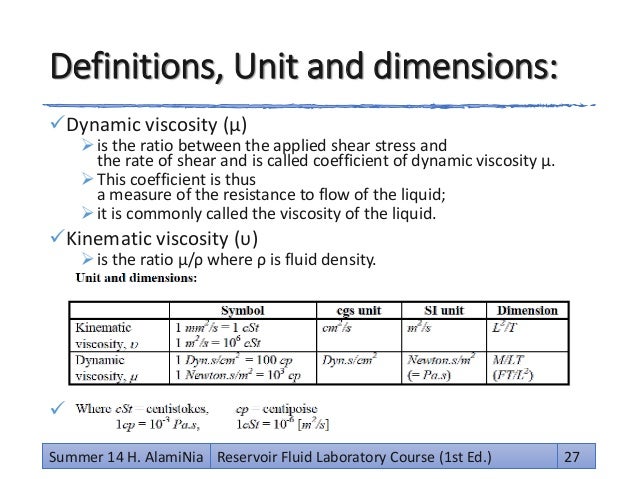

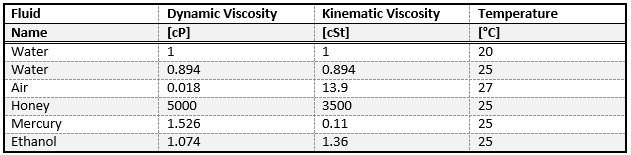

The kinematic viscosity in cSt at 40☌ is the basis for the ISO 3448 kinematic viscosity grading system, making it the international standard. Several engineering units are used to express viscosity, but the most common by far are centistoke (cSt) for kinematic viscosity and the centipoise (cP) for dynamic (absolute) viscosity. Typically, viscosity is reported at 40☌ and/or 100☌ or both if the viscosity index is required.

The temperature must be defined to interpret the viscosity reading. Likewise, reporting viscosity for trending purposes without a reference to temperature is nonsensical. Viscosity is not a dimensional measurement, so calling highly viscous oil thick and less viscous oil thin is misleading. Sometimes, viscosity is erroneously referred to as thickness (or weight). Generally speaking, viscosity is a fluid’s resistance to flow (shear stress) at a given temperature. Given the importance of viscosity analysis coupled with the increasing popularity of onsite oil analysis instruments used to screen and supplement offsite laboratory oil analysis, it is essential that oil analysts clearly understand the difference between absolute and kinematic viscosity measurements.

By contrast, most onsite viscometers measure absolute viscosity, but are typically programmed to estimate and report kinematic viscosity, so that the viscosity measurements reported reflect kinematic numbers reported by most labs and lube oil suppliers. Most used oil analysis laboratories measure and report kinematic viscosity.

The two are easily confused, but are significantly different. Viscosity can be measured and reported as dynamic (absolute) viscosity or as kinematic viscosity. However, there is more to viscosity than meets the eye. Likewise, there is no property more critical to effective component lubrication than base oil viscosity. Of all the tests employed for used oil analysis, none provides better test repeatability or consistency than viscosity.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)